|

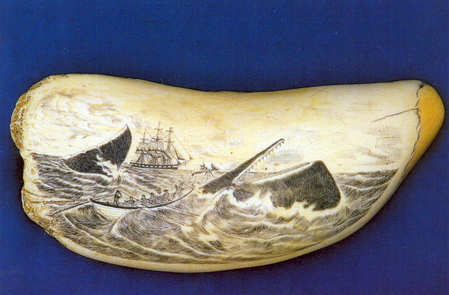

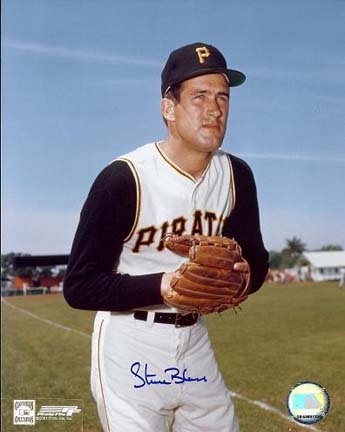

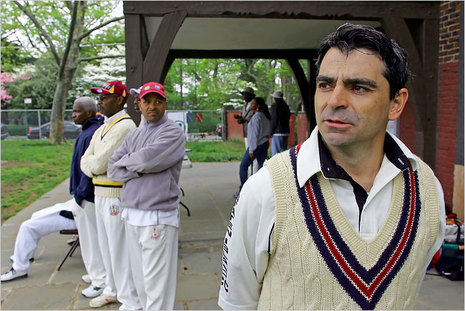

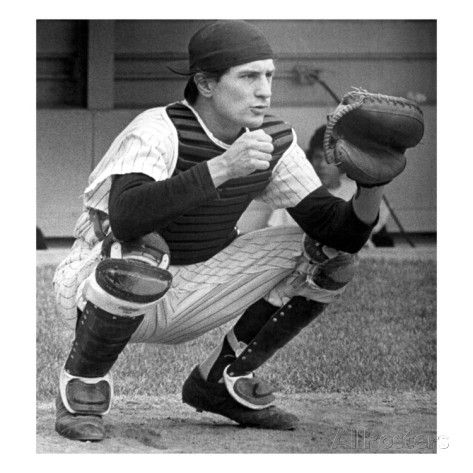

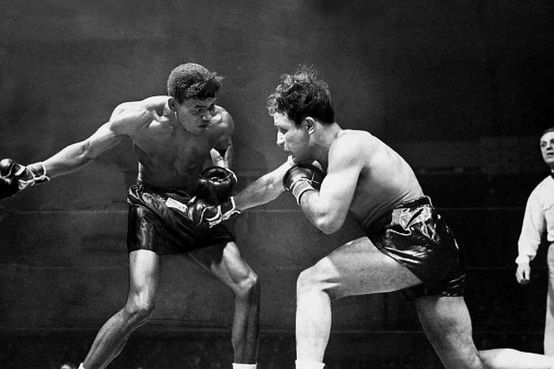

When Chad Harbach’s The Art of Fielding was published in 2011, it was hailed as The Great Sports Novel. The review pages outdid each other in their praises. Jonathan Franzen and Jay McInerney contributed cover blurbs. The novel shot up the New York Times bestseller list. Amazon.com named it the Book of the Year. I didn’t like it much. The 500-page narrative centres on the Westish Harpooners, the baseball team of a small liberal arts college in Wisconsin. The novel spans an unusually successful season for the side, and their games provide the backbone of the story. But I never felt that Harbach’s heart was in the sporting action. He was far more interested in the other games he was playing in the book. The Art of Fielding is in the tradition of the whimsical campus novel. The characters display a two-dimensional preciousness, heightened by their abnormal levels of self-awareness. They are positively knowing in their reflexivity. When the heterosexual president of the college embarks on a gay affair with the team’s star batter, he can scarcely lift a cup without reflecting on how he is conducting himself. His daughter drops out and experiments with a range of new personae. The team’s captain wonders which of his psychic guises is best-suited to galvanizing his team. When these last two get together, they become giddy with the range of roles available to them. And then there is Harbach’s own authorial self-awareness. As an English graduate of Harvard, and founder and editor of the East Coast literary magazine n+1, he might be expected to furnish his novel with literary motifs. He doesn’t disappoint. Melville and Moby Dick feature prominently, and other bookish signposts are dotted around for the attentive reader. The only person within sight who isn’t weighed down by self-consciousness is Henry Skrimshander, the talismanic shortstop who is largely responsible for the Harpooners’ atypical success. Notwithstanding his cutesy Melvillian surname, Henry is a cipher-like savant whose only distinguishing feature is his unnatural ability to gather up ground balls and spear them across the field to first base. Except that . . . halfway through the season Henry unaccountably lets go a wild throw and injures a teammate. He starts to worry about his throwing technique and his performance deteriorates. The more he tries, the worse it gets. He has to be replaced in the team. In short, he becomes disabled by the Yips. Isn’t that ironic? The one person around who isn’t self-conscious is laid low by anxiety about his skills. Just in case you missed the point, Harbach pummels it home with a chapter on post-modernism and the Yips. The pitcher Steve Blass first succumbed to his eponymous disease in 1973, the same year as Watergate and the publication of Gravity’s Rainbow. Perhaps this marked the moment when artistic self-awareness seeped into the general culture and destroyed the innocence of the average citizen. In Harbach’s words: “In fact, that might make for a workable definition of the post-modernist era: an era when even the athletes were anguished Moderrnists. In which case the American post-modern period began in spring 1973, when a pitcher named Steve Blass lost his arm.” For heaven’s sake. The Yips are real, not some academic fad. When The Art of Fielding first came out, Vanity Fair published a long behind-the-scenes piece by Keith Gessen, a friend of Harbach’s, about the run-up to publication. Among other things, the article addressed the issue of how a first novelist managed to command an advance of $650,000. “We knew so many people,” explained Gessen. No doubt these acquaintances loved the way that Harbach’s book made a literary trope out of baseball. But it didn’t add up to what I’d call a sports novel. Still, perhaps it’s not surprising that Harbach’s novel was greeted as a leader in the sporting stakes. It is not as if there is a lot of competition. Sport plays as big a role in many people’s lives as romance, or work, or politics. Yet for some reason it doesn’t lend itself to fictionalizing. For all the many novels about thwarted love, disputed money, and the forces of history, there are scarcely that hinge on who will win the big match. Of course, there are plenty of fine novels in which sport provides a motif or minor theme. For example, Don DeLillo’s Underworld starts with the “Shot Heard Round World”, the home run that took the New York Giants to the World Series in 1951, and the fate of the ball dispatched into the crowd provides a recurring theme through the book. Similarly, much of David Foster Wallace’s Infinite Jest, published the previous year in 1996, is set in a residential tennis academy, and Foster has plenty to say about the sport. But that’s not enough to make them sports novels. You wouldn’t expect to find them in the sports section in the bookshop. They might talk about sports in passing, but their main concerns lie elsewhere. I’d say the same about two excellent recent novels that do often get classified as sports books. The protagonist of Joseph O’Neill’s Netherland is a Dutch financial analyst living in New York in the years around the destruction of the World Trade Center. He falls in with the cricket-playing community, nearly all Asian and West Indian, but finds that he must adjust his batting technique, and much else besides, to cope with the bumpy terrain he finds in the city. In Shihan Karunatilaka’ Chinaman (the Legend of Pradeep Matthew in the States), a decrepit sportswriter tries to track down a spin-bowling prodigy whom the Sri Lankan cricket authorities have mysteriously expunged from the records. The search ranges high and low through Sri Lankan society, taking in elite schools, television politics, betting corruption, and hard-drinking expatriates. While cricket is central to both these books, I still wouldn't count them as sports novels. Cricket might provide the theme, but the authors have other fish to fry. No matches enter into the narrative, no wins or losses matter to the characters’ fortunes. The novels aren’t concerned with sporting contests, so much as with the wider societies in which they take place. Why are genuine sports novels so thin on the ground? Perhaps the problem is the distance between sport and the rest of life. Sporting contests tends to be encapsulated from other things that matter. For the most part, what happens on the playing field stays on the playing field. That’s one possible explanation. A novel that centered on the outcomes of sporting encounters would struggle to connect up with the rest of its characters’ lives. But I remain puzzled. Maybe the encapsulation of sport explains why it doesn’t play a central role in any mainstream literary novels. Still, why isn’t there at least a genre of specifically sporting novels? Not all novels aim to cast light on the general human condition. As many are designed to fuel their readers’ fantasies. Romance fiction offers heroines whose virtues overcome adversity and are rewarded with love. Detective stories are for those who dream about conquering evil by the power of intellect. Science fiction, Westerns and thrillers cater to yet other aspirations. This isn't to say that genre novels leave no space for other literary virtues. But their first priority is to give substance to their readers’ daydreams. Sport would seem to offer a perfect opportunity for this kind of writing. All sports enthusiasts dream of winning, if not Wimbledon, then at least the summer cup at the local club. So why aren’t there tales of derring-do on the sports field, written for readers eager to experience the rewards of victory at second-hand? But that’s not how it seems to work. When novels do make a narrative out of sporting events, scarcely any come out as straight aspirational fiction. Instead they tend to retreat into mythic otherworldliness, or knockabout comedy, or both. Somehow the authors seem unable to take their subject matter as given, but must address it at arm’s length. The classic example of the sporting novel as myth is Bernard Malamud’s The Natural. Though this draws on incidents from the history of baseball, its main inspiration is the Arthurian legend. Characters stand for romantic knights, and the league pennant signifies the Holy Grail. The style follows suit, and creates an impression of observing the action through thin gauze. The Natural isn’t an isolated case. The same ghostly atmosphere pervades The Book of Fame by Loyd Jones, based on the triumphant 1905 "Originals", the first All Blacks rugby team from New Zealand to visit the British Isles, and The Damned Utd, David Peace’s treatment of Brian Clough’s brief interlude as manager of Leeds United in 1974. They’re both terrific books, but their short poetic sentences abandon realistic detail for a hazy recreation of past times. I’d put Mark Harris’s much-loved quartet of baseball novels (The Southpaw, Bang the Drum Slowly, . . .) in the same category. They tell a good if sometimes mawkish story, but the device of a narrator who is semi-literate and none too perceptive places the reader at a distance and blots out the action. The other common species of sports novel is the humorous. These don’t always stand the test of time. One of the earliest was Ring Lardner’s 1914 You Know Me Al, a fictional chronicle of big-league pitcher Jack Keefe, in which the main joke is how this bumptious rube is manipulated by everyone around him. The book was a big hit at the time, but a century later it comes across as little more than mean-spirited and patronizing. Dan Jenkins’ successful sports comedies (Semi-Tough about gridiron and Dead Set Perfect about golf) have suffered a similar fate—much of what might have seemed funny in the 1970s will now strike most readers as sexist, racist or worse. Not all sporting humour becomes dated. The golfing stories of P.G. Wodehouse are as fresh as when they were written in the 1920s. His two golfing collections, The Clicking of Cuthbert and The Heart of a Goof are among his best work, packed with gems like the man who “missed short putts because of the uproar of the butterflies in the adjoining meadows”. Wodehouse was a golf nut himself, and the stories conceal eternal verities behind their farcical plots. And then there is Philip Roth’s The Great American Novel, which manages to be both mythic and comic at the same time. It tells the story of a fictional baseball league during World War II. It’s perhaps the least-read of Roth’s books, not least because it makes no concessions to readers who aren’t baseball aficionados. But for those who can penetrate the arcana, I’d say it is up there with Portnoy’s Complaint among Roth’s early, funny books. One of the many good things about Roth’s book is that it’s the first place I came across sabermetrics. The son of one of the team’s owners is a self-styled “17 year-old Jewish genius”. He tells the players and the manager of his father’s baseball team that they’re doing it all wrong, they really shouldn’t be making sacrifice bunts, it’s costing them 60 runs a year, and all those intentional walks, that’s even worse. But despite his graphs and numbers the players and manager think he’s nuts, and just tell him to go away. Roth’s book was written in 1973, and he credits Earnshaw Cook, an engineering professor who’d written about these sabermetric ideas back in the 1960s. That’s 40 years before Billy Beane and Moneyball. It’s amazing that this information was out there for so long before anybody in baseball took any notice. But let’s get back to the issue of why so few sporting novels tell it straight, rather than creating myths or telling jokes. Perhaps the answer is that there’s no call for the service that they would provide. If you want to identify with protagonists in a sporting narrative, what’s wrong with the real thing? In the modern world, sports enthusiasts have every opportunity to follow the real-life fortunes of their sporting heroes. Perhaps this crowds out any demand for fictional substitutes. The trouble with this theory is that there are plenty of successful sporting fictions outside the world of grown-up novels. Take children’s fiction for a start. A lively tradition of novels has long been available for young sports fans. P.G. Wodehouse himself started with cricket stories set in public schools, and in the 1930s John R. Tunis matched him in the States with a series of baseball stories featuring the Brooklyn Dodgers. Contemporary equivalents include Michael Hardcastle, particularly his soccer stories featuring Gary Ansell, and John Feinstein’s sequence of thrillers set across a range of American sports. Movies also seem to have no difficulty in telling sports stories. Some of these are real turkeys, of course: Knut Rockne: All-American with Ronald Reagan; the later Rocky movies (though there’s nothing wrong with the original); The Legend of Bagger Vance; Escape to Victory. Still, for every bad sports movie there are plenty of good ones. My favourites include The Pride of the Yankees, Breaking Away, Bull Durham, and the glorious Tin Cup. (What about Martin Scorcese’s Raging Bull? Many would rank that top. I can recognize its virtues, but I never warmed to it. When I was a kid in South Africa in the 1950s, I was a junior boxer and a huge fan. Sugar Ray Robinson, Rocky Graziano, Jake LaMotta – the very names glowed in lights from across the ocean. But to Scorcese, LaMotta was a slob sitting in a kitchen in his vest. I couldn’t help feeling that he didn’t properly appreciate the stature of his subject.) Anyway, whichever films we rank as our favourites, there’s no doubt that cinema, along with children’s fiction, lends itself to realistic sporting narratives. So why can’t ordinary sports novels fill this role too? It can’t be that there in no demand for stories that hinge on who wins and loses.

I think I have an answer. The clue lies in the few grown-up books that do succeed as straight sports novels. Here are a handful of proper books where the results of sporting contests matter This Sporting Life by David Storey; Fat City by Leonard Gardner; North Dallas Forty by Pete Gent; The Rider by Tim Crabbe. No doubt there are more. I certainly haven’t read every novel with a sporting theme. But if there are other straight sports novels worth reading, I bet that they share a feature with these four. The authors will know their subject matter at first hand. They will have lived the life they are writing about. Storey was a professional rugby league player with Leeds (now Leeds Rhinos) for five years in the 1950s; Gardner grew up around the boxing gyms in Stockton, California and fought himself; Gent played wide receiver for the Dallas Cowboys from 1964 to 1968; Krabbe was a top amateur cyclist who competed in 100-kilometer-plus road races. As any reader will quickly discern, not a page of their books could have been written without this first-hand experience. Writers of novels need experience to supply the background. In films and children’s fiction, the action can be graphic and sketchy. But novels are necessarily denser, even those without literary pretensions. You need details to add verisimilitude to the narrative. That is why sporting novels written by fans rather than players inevitably collapse into fables or jokes. Without any direct acquaintance with their topics, non-athletes are unable to sustain a realistic treatment. They need to fabricate a world to keep the story going, and find themselves with the choice between fairy-tale or farce. So in the end there’s an obvious solution to our original puzzle. The reason good sports novels are so thin on the ground is that they need writers who have both been serious athletes and are capable of writing fiction. Each category is small enough on its own. Their overlap must be tiny. As a group, novelists are not known for their athletic prowess. Nor are committed athletes the first constituency you would turn to unearth literary talent. If you think about it, it’s something of a miracle that there are any good sports novels at all. The two essential qualifications for writing them pull strongly against each other. We should be grateful for the few that we do have.

21 Comments

|

AuthorI am interested in nearly all sports from around the world. I used to play some but not so much any more. Previous Posts (only 6 & 17 are still live links-see main text) 1 Choking, The Yips and Not Having Your Mind Right 2 Mutual Aid and the Art of Road Cycle Racing 3 Why Supporting a Team isn't Like Choosing a Washing Machine 4 Civil Society and Why Adnan Januzaj Should be Eligible for England (Though He Isn't) 5 Why Does Test Cricket Run in Families? 6 Bruce Grobbelaar and Middle Class Morality 7 The Importance of Being Focused 8 Professional Fouls and Political Obligation 9 Morality, Convention and Football Fakery 10 Give Me a Defender of Amateur Values and I'll Show You a Hypocrite 11 Game Theory, Team Reasoning, and a Bit about Sport Too 12 Sporting Geography, Political Geography and the Ryder Cup 13 Competitive Balance, Coase's Theorem and Sporting Capitalism 14 Bill Shankly, Noam Chomsky and the Value of Sport 15 Sporting Teams, Spacetime Worms, and Israeli Football 16 Race, Ethnicity and Joining the Club 17 Myth, Humour and the Strange Dearth of Sports Novels Archives

March 2017

CategoriesBlogrolling

Stephen Law

Editor of Think, philosophy, humanism Think Tonk

Clayton Littlejohn, epistemologist and colleague Philosophers' Carnival

Monthly digest of highspots from the philosophy blogosphere Philosophy Football

"Sporting outfitters of intellectual distinction." T-shirts and theses about football. |