|

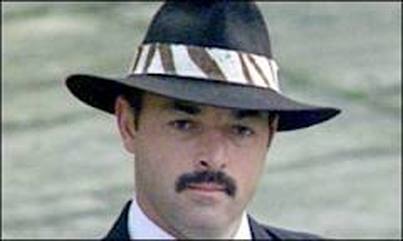

This one is especially for Liverpool fans and legal eagles. But it also carries some general morals for anyone interested in the relations between the law, morality, and the jury system. Remember Bruce Grobbelaar, Liverpool goalie in the 1980s and 90s? Big moustache, did that wobbly knees thing in the 1984 European Cup final, looked like he ran some dodgy Zimbabwean safari firm? Well—for a while he did run a dodgy Zimbabwean safari firm, and that turned out to be the start of his troubles. In the early 1990s, while still playing for Liverpool, Grobbelaar met a fellow Zimbabwean, Christopher Vincent, who induced him to invest £55,000 in a safari camp. When the business failed, the resourceful Mr Vincent, loath to lose his meal ticket, recalled some late-night snippets Bruce had revealed about shady dealings with betting rings, and went to the Sun with the story. The newspaper promptly equipped Vincent with tape recorders and cash. Secret recordings were made in borrowed apartments. And in due course the Sun ran a series of big splashes alleging that Grobbelaar had taken money from Vincent and others to throw games. Wobbly knees European Cup final 1984 Taking bribes to fix matches is a criminal act, and so soon afterwards Bruce found himself in the dock of Winchester Crown Court. However, the prosecution struggled to secure a conviction. In a first trial the jury failed to reach any verdict, and in a retrial later the same year another jury acquitted Grobbelaar on one charge and couldn’t agree on another—at which point the prosecution gave the whole thing up as a bad job. Grobbelaar did well to escape jail. There was plenty of evidence against him, and the fact that Vincent had been an agent provocateur was no defence. Moreover, it was hard to attach much credence to Grobbelaar’s story that he had only been playing along with Vincent to find out who was behind him, especially as this tale didn’t answer the allegations involving other betting syndicates. The only real thing going for the defence was that the instrument of Grobbelaar’s downfall was the Sun. As the jury would have known, the Sun had been conducting a vendetta against Liverpool football club for some years. After the Hillsborough disaster in 1989, it repeatedly trumpeted the smears about Liverpool fans that the police had invented to cover up their own responsibility for the ninety-six deaths. Nor was it above bringing Grobbelaar’s wife Deb and children into the bribery splashes. “Shameful secret has Deb in tears” ran one headline, and another article reported that Grobbelaar had refused to answer such reporter’s questions as "How much of what's been happening have you told the children about? Have they been getting a hard time at school?" We can imagine that the jury might well have felt disinclined to kick a man who’d been subject to such treatment. Grobbelaar’s successes in the criminal courts encouraged him to go on the offensive. He sued the Sun for libel, and in 1999 a jury found for him in the High Court and awarded him £85,000 in damages. (I hope you aren’t getting tired of all these trials. I warned you that this was one for the legal buffs. There are still two more verdicts to come.) The Sun promptly appealed against the libel decision, on the grounds that the jury’s verdict was ‘perverse’. This was somewhat unusual, in that jury decisions are close to sacrosanct in English-based common law, and normally you can’t appeal just on the basis the jury got it wrong. But in certain kinds of cases you can get a jury verdict overturned if you can show that ‘no reasonable jury, who had applied their minds properly to the facts of the case, could have arrived at the conclusion which was reached’. And that’s what the Sun successfully argued in the Court of Appeal. Remember that in civil libel cases the defendants—the alleged libellers—only need to prove the truth of their claims ‘on the balance of the probabilities’, and not ‘beyond the reasonable doubt’ required for a criminal conviction. So the Sun could concede that their incriminating tapes and other evidence might not have been enough to compel the criminal juries in Winchester, and yet insist that any reasonable person would take them to show that Grobbelaar’s guilt was at least more probable than not. The Court of Appeal agreed, striking down the jury’s verdict and the £85,000. We aren’t done yet. By now Bruce had the bit between his teeth, and opted to take it all the way to the top, to what would now be the Supreme Court, but was then the Law Lords. Once they got their hands on the case, the Lords of Appeal in Ordinary started by thinking a bit harder about what the original libel jury could have had in mind. They noted that there were two distinct parts to the Sun’s allegations. In the first place the Sun had said that Grobbelaar had been accepting bribes. And then they had said that he had let in goals on purpose. The Law Lords came to the view that the jury must have thought that, while there was plenty evidence for the first claim, there wasn’t any for the second, and that they had found against the Sun for that reason. In truth, not only was there no evidence that Bruce had let in goals, but good evidence that he hadn’t. Let me quote from the Law Lords’ eventual written opinions. (You can read all their 20,000 words at http://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/ld200102/ldjudgmt/jd021024/grobb-1.htm.) Here’s a passage about witnesses at the libel trial: “There was expert evidence strongly supportive of the appellant's evidence from Mr Bob Wilson, formerly a professional goalkeeper of the highest standing, and Mr Alan Ball, formerly a professional footballer of renown who had been the appellant's manager at Southampton. Mr Wilson saw no evidence of anything other than good (and on occasion outstanding) goalkeeping in any of the five games. Mr Ball saw nothing odd or suspicious in the appellant's play in either of the two Southampton games, both of which he had watched.” Yes, these dudes really do write like that. ‘Formerly a professional footballer of renown.’ Alan Ball. I am sure that most senior judges are regular human beings who only use such phrases that because they enjoy celebrating the old forms. But in this particular instance, as we are about to see, the sitting Lords of Appeal in Ordinary did little to dispel the impression that they were a bunch of old fogeys who’d been living with their pompous phraseology for a long time, handing down rulings and feeling entitled to impose their views on the rest of us. Taking account of the expert evidence from Ball and Wilson, the Law Lords upheld the original jury’s verdict that the Sun was guilty of libel. They reasoned that the jury must have felt that the Sun hadn’t shown that Grobbelaar had let in goals on purpose, and moreover that this justified an award of £85,000. However, the Lords disagreed strongly with jury about the second part. They allowed that the Sun hadn’t proved their claims about the goals, and that these claims were libellous. But they didn’t think that these claims damaged Grobbelaar in any substantial way—on the grounds that his name was already mud. As they saw it, he had already been exposed as someone who had taken bribes on the promise of fixing games. That he was then falsely said to have let in goals as well could scarcely damage him further, as he had no reputation left to protect. So they awarded him a nominal £1 and required him to pay all costs. Grobbelaar declared himself bankrupt soon afterwards.

I don’t know how it was for you, but when I first read the original Sun stories I was shocked. It wasn’t the bribery that shocked me, though, so much as the thought that Bruce might have thrown games on purpose. All right, taking bribes isn’t very nice, and certainly it lowered Bruce considerably in my estimation. He was clearly hanging out with an unsavoury crowd. But that wasn’t in the same ball-park as losing games on purpose. How could he have let down his teammates, the fifty thousand desperate fans on the Kop behind him, the whole history of Liverpool football club, just for a few pounds? No punishment would be enough for someone who did that. He should be cast out and left to wander in the wilderness for the rest of his days. Well, that’s not how the Law Lords saw it. Lord Hobhouse was quite explicit on the point. “Corruption is much more serious than letting in goals deliberately. The one is a criminal offence and the other, as such, is not.” Perhaps it’s not surprising that men who have spent their whole life administering the law should regard breaking it as a paramount sin. But someone who was brought up in Zimbabwe, or on the wrong side of the tracks in Liverpool, or in many other places, might well take a different view, holding that while a lot of laws are sensible, a lot are also designed to preserve the interests of privileged groups, and that therefore breaking the law isn’t necessarily the worst thing in the world, compared with cheating your mates, say, or letting down the fans. Still, this is a topic on which different opinions are possible, and the eminent Lords were perfectly entitled to their view. What they weren’t entitled to do, though, was correct the original jury on the matter. The law of libel is complicated. An appeal court has the power to reduce the amount of damages awarded by a jury if they feel that it is an excessive departure from previous such awards. But that clearly wasn’t the issue in this case, though the Law Lords pretended that it was. It wasn’t that they felt that the jury had misjudged how much money to award for a serious libel. Rather they felt that the jury were wrong to think that there was a serious libel in the first place. And this was absolutely not their business. The law of defamation says that your published words are libellous if they will ‘lower someone in the estimation of right-thinking members of society generally’. By the Law Lords' own analysis, the jury felt that the allegations that Grobbelaar had thrown games on purpose indeed lowered him substantially in the eyes of right-thinking people generally, even against the background of his taking bribes. I myself think that the jury was absolutely right about this. To normal right-thinking people, the idea of Grobbelaar deliberately missing the ball in front of the Kop would be horrendous, far worse than taking bribes. But that’s not the point. Whether the jury was right or wrong, it was a matter for them to decide, and the Law Lords had no right to substitute their own view of what ‘right-thinking members of society generally’ would think for that of the jury. I am not sure what to make of this. Whatever their other failings, the Law Lords were not stupid, and they must have known in their hearts that they were riding roughshod over the law on juries. It is a basic principle of our legal system that, ‘perversity’ aside, appeal judges cannot correct the conclusions that juries reach about matters of fact. In the end, it is hard not to see something almost hypocritical in their decision. Having appealed to the importance of the law against bribery to override the jury’s view that Grobbelaar had been badly libelled by the standards of everyday morality, the Law Lords then allowed their own moral attitudes to override their duty to the law. Of course the law wasn’t the only thing damaged by the Law Lords’ decision. It also ruined Grobbelaar financially. But Bruce is nothing if not resilient. Over the years he has moved around, coaching a series of teams in South Africa, England and then Canada, where he is now settled. He remains a great favourite at Anfield, turning out regularly for the 5 Times Liverpool Legends team (five times European champions, if you’re wondering), and in 2006 he was voted number 17 in the official club poll of all-time favourite players. Clearly the Liverpool fans don’t think that he let in goals on purpose. Nor do I.

12 Comments

|

AuthorI am interested in nearly all sports from around the world. I used to play some but not so much any more. Previous Posts (only 6 & 17 are still live links-see main text) 1 Choking, The Yips and Not Having Your Mind Right 2 Mutual Aid and the Art of Road Cycle Racing 3 Why Supporting a Team isn't Like Choosing a Washing Machine 4 Civil Society and Why Adnan Januzaj Should be Eligible for England (Though He Isn't) 5 Why Does Test Cricket Run in Families? 6 Bruce Grobbelaar and Middle Class Morality 7 The Importance of Being Focused 8 Professional Fouls and Political Obligation 9 Morality, Convention and Football Fakery 10 Give Me a Defender of Amateur Values and I'll Show You a Hypocrite 11 Game Theory, Team Reasoning, and a Bit about Sport Too 12 Sporting Geography, Political Geography and the Ryder Cup 13 Competitive Balance, Coase's Theorem and Sporting Capitalism 14 Bill Shankly, Noam Chomsky and the Value of Sport 15 Sporting Teams, Spacetime Worms, and Israeli Football 16 Race, Ethnicity and Joining the Club 17 Myth, Humour and the Strange Dearth of Sports Novels Archives

March 2017

CategoriesBlogrolling

Stephen Law

Editor of Think, philosophy, humanism Think Tonk

Clayton Littlejohn, epistemologist and colleague Philosophers' Carnival

Monthly digest of highspots from the philosophy blogosphere Philosophy Football

"Sporting outfitters of intellectual distinction." T-shirts and theses about football. |