|

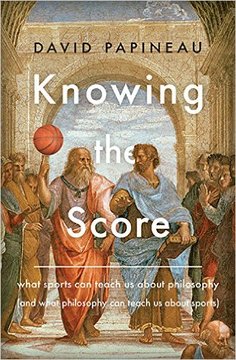

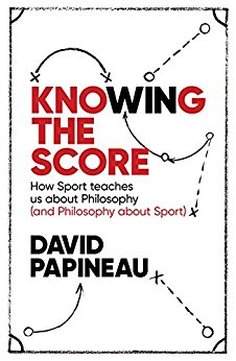

My book Knowing the Score was published in May 2017. It looks at a range of sporting themes from a philosophical angle, and explores a range of philosophical topics as they arise in sporting contexts. As the dust jacket says: 'It is perfect reading for armchair philosophers and sporting enthusiasts alike.' That's the US edition on the left, with the UK edition on the right.

Much of the the book is loosely based on material I have posted on this blog over the past few years. This material will no longer be available here, though I have left up a couple of posts that weren't used for the book. (I have also preserved the old list of 'Previous Posts' on the right, as a memento, and as a taster for the book, but only 6 & 17 (which weren't used in the book) are still live links. If by any chance somebody wants to check something from the removed posts, just ask--I can still access them myself.)

13 Comments

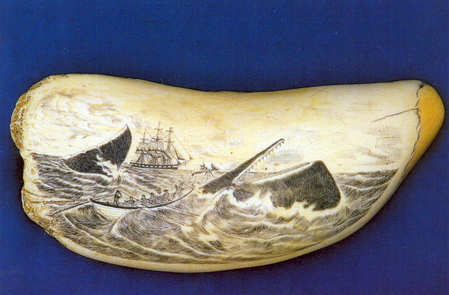

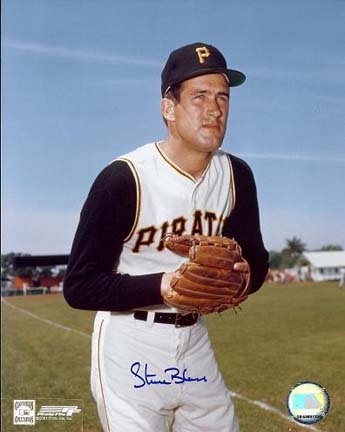

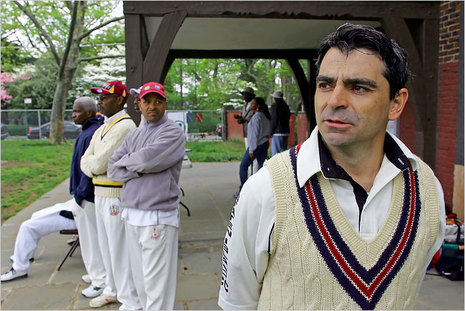

When Chad Harbach’s The Art of Fielding was published in 2011, it was hailed as The Great Sports Novel. The review pages outdid each other in their praises. Jonathan Franzen and Jay McInerney contributed cover blurbs. The novel shot up the New York Times bestseller list. Amazon.com named it the Book of the Year. I didn’t like it much. The 500-page narrative centres on the Westish Harpooners, the baseball team of a small liberal arts college in Wisconsin. The novel spans an unusually successful season for the side, and their games provide the backbone of the story. But I never felt that Harbach’s heart was in the sporting action. He was far more interested in the other games he was playing in the book. The Art of Fielding is in the tradition of the whimsical campus novel. The characters display a two-dimensional preciousness, heightened by their abnormal levels of self-awareness. They are positively knowing in their reflexivity. When the heterosexual president of the college embarks on a gay affair with the team’s star batter, he can scarcely lift a cup without reflecting on how he is conducting himself. His daughter drops out and experiments with a range of new personae. The team’s captain wonders which of his psychic guises is best-suited to galvanizing his team. When these last two get together, they become giddy with the range of roles available to them. And then there is Harbach’s own authorial self-awareness. As an English graduate of Harvard, and founder and editor of the East Coast literary magazine n+1, he might be expected to furnish his novel with literary motifs. He doesn’t disappoint. Melville and Moby Dick feature prominently, and other bookish signposts are dotted around for the attentive reader. The only person within sight who isn’t weighed down by self-consciousness is Henry Skrimshander, the talismanic shortstop who is largely responsible for the Harpooners’ atypical success. Notwithstanding his cutesy Melvillian surname, Henry is a cipher-like savant whose only distinguishing feature is his unnatural ability to gather up ground balls and spear them across the field to first base. Except that . . . halfway through the season Henry unaccountably lets go a wild throw and injures a teammate. He starts to worry about his throwing technique and his performance deteriorates. The more he tries, the worse it gets. He has to be replaced in the team. In short, he becomes disabled by the Yips. Isn’t that ironic? The one person around who isn’t self-conscious is laid low by anxiety about his skills. Just in case you missed the point, Harbach pummels it home with a chapter on post-modernism and the Yips. The pitcher Steve Blass first succumbed to his eponymous disease in 1973, the same year as Watergate and the publication of Gravity’s Rainbow. Perhaps this marked the moment when artistic self-awareness seeped into the general culture and destroyed the innocence of the average citizen. In Harbach’s words: “In fact, that might make for a workable definition of the post-modernist era: an era when even the athletes were anguished Moderrnists. In which case the American post-modern period began in spring 1973, when a pitcher named Steve Blass lost his arm.” For heaven’s sake. The Yips are real, not some academic fad. When The Art of Fielding first came out, Vanity Fair published a long behind-the-scenes piece by Keith Gessen, a friend of Harbach’s, about the run-up to publication. Among other things, the article addressed the issue of how a first novelist managed to command an advance of $650,000. “We knew so many people,” explained Gessen. No doubt these acquaintances loved the way that Harbach’s book made a literary trope out of baseball. But it didn’t add up to what I’d call a sports novel. Still, perhaps it’s not surprising that Harbach’s novel was greeted as a leader in the sporting stakes. It is not as if there is a lot of competition. Sport plays as big a role in many people’s lives as romance, or work, or politics. Yet for some reason it doesn’t lend itself to fictionalizing. For all the many novels about thwarted love, disputed money, and the forces of history, there are scarcely that hinge on who will win the big match. Of course, there are plenty of fine novels in which sport provides a motif or minor theme. For example, Don DeLillo’s Underworld starts with the “Shot Heard Round World”, the home run that took the New York Giants to the World Series in 1951, and the fate of the ball dispatched into the crowd provides a recurring theme through the book. Similarly, much of David Foster Wallace’s Infinite Jest, published the previous year in 1996, is set in a residential tennis academy, and Foster has plenty to say about the sport. But that’s not enough to make them sports novels. You wouldn’t expect to find them in the sports section in the bookshop. They might talk about sports in passing, but their main concerns lie elsewhere. I’d say the same about two excellent recent novels that do often get classified as sports books. The protagonist of Joseph O’Neill’s Netherland is a Dutch financial analyst living in New York in the years around the destruction of the World Trade Center. He falls in with the cricket-playing community, nearly all Asian and West Indian, but finds that he must adjust his batting technique, and much else besides, to cope with the bumpy terrain he finds in the city. In Shihan Karunatilaka’ Chinaman (the Legend of Pradeep Matthew in the States), a decrepit sportswriter tries to track down a spin-bowling prodigy whom the Sri Lankan cricket authorities have mysteriously expunged from the records. The search ranges high and low through Sri Lankan society, taking in elite schools, television politics, betting corruption, and hard-drinking expatriates. While cricket is central to both these books, I still wouldn't count them as sports novels. Cricket might provide the theme, but the authors have other fish to fry. No matches enter into the narrative, no wins or losses matter to the characters’ fortunes. The novels aren’t concerned with sporting contests, so much as with the wider societies in which they take place. Why are genuine sports novels so thin on the ground? Perhaps the problem is the distance between sport and the rest of life. Sporting contests tends to be encapsulated from other things that matter. For the most part, what happens on the playing field stays on the playing field. That’s one possible explanation. A novel that centered on the outcomes of sporting encounters would struggle to connect up with the rest of its characters’ lives. But I remain puzzled. Maybe the encapsulation of sport explains why it doesn’t play a central role in any mainstream literary novels. Still, why isn’t there at least a genre of specifically sporting novels? Not all novels aim to cast light on the general human condition. As many are designed to fuel their readers’ fantasies. Romance fiction offers heroines whose virtues overcome adversity and are rewarded with love. Detective stories are for those who dream about conquering evil by the power of intellect. Science fiction, Westerns and thrillers cater to yet other aspirations. This isn't to say that genre novels leave no space for other literary virtues. But their first priority is to give substance to their readers’ daydreams. Sport would seem to offer a perfect opportunity for this kind of writing. All sports enthusiasts dream of winning, if not Wimbledon, then at least the summer cup at the local club. So why aren’t there tales of derring-do on the sports field, written for readers eager to experience the rewards of victory at second-hand? But that’s not how it seems to work. When novels do make a narrative out of sporting events, scarcely any come out as straight aspirational fiction. Instead they tend to retreat into mythic otherworldliness, or knockabout comedy, or both. Somehow the authors seem unable to take their subject matter as given, but must address it at arm’s length. The classic example of the sporting novel as myth is Bernard Malamud’s The Natural. Though this draws on incidents from the history of baseball, its main inspiration is the Arthurian legend. Characters stand for romantic knights, and the league pennant signifies the Holy Grail. The style follows suit, and creates an impression of observing the action through thin gauze. The Natural isn’t an isolated case. The same ghostly atmosphere pervades The Book of Fame by Loyd Jones, based on the triumphant 1905 "Originals", the first All Blacks rugby team from New Zealand to visit the British Isles, and The Damned Utd, David Peace’s treatment of Brian Clough’s brief interlude as manager of Leeds United in 1974. They’re both terrific books, but their short poetic sentences abandon realistic detail for a hazy recreation of past times. I’d put Mark Harris’s much-loved quartet of baseball novels (The Southpaw, Bang the Drum Slowly, . . .) in the same category. They tell a good if sometimes mawkish story, but the device of a narrator who is semi-literate and none too perceptive places the reader at a distance and blots out the action. The other common species of sports novel is the humorous. These don’t always stand the test of time. One of the earliest was Ring Lardner’s 1914 You Know Me Al, a fictional chronicle of big-league pitcher Jack Keefe, in which the main joke is how this bumptious rube is manipulated by everyone around him. The book was a big hit at the time, but a century later it comes across as little more than mean-spirited and patronizing. Dan Jenkins’ successful sports comedies (Semi-Tough about gridiron and Dead Set Perfect about golf) have suffered a similar fate—much of what might have seemed funny in the 1970s will now strike most readers as sexist, racist or worse. Not all sporting humour becomes dated. The golfing stories of P.G. Wodehouse are as fresh as when they were written in the 1920s. His two golfing collections, The Clicking of Cuthbert and The Heart of a Goof are among his best work, packed with gems like the man who “missed short putts because of the uproar of the butterflies in the adjoining meadows”. Wodehouse was a golf nut himself, and the stories conceal eternal verities behind their farcical plots. And then there is Philip Roth’s The Great American Novel, which manages to be both mythic and comic at the same time. It tells the story of a fictional baseball league during World War II. It’s perhaps the least-read of Roth’s books, not least because it makes no concessions to readers who aren’t baseball aficionados. But for those who can penetrate the arcana, I’d say it is up there with Portnoy’s Complaint among Roth’s early, funny books. One of the many good things about Roth’s book is that it’s the first place I came across sabermetrics. The son of one of the team’s owners is a self-styled “17 year-old Jewish genius”. He tells the players and the manager of his father’s baseball team that they’re doing it all wrong, they really shouldn’t be making sacrifice bunts, it’s costing them 60 runs a year, and all those intentional walks, that’s even worse. But despite his graphs and numbers the players and manager think he’s nuts, and just tell him to go away. Roth’s book was written in 1973, and he credits Earnshaw Cook, an engineering professor who’d written about these sabermetric ideas back in the 1960s. That’s 40 years before Billy Beane and Moneyball. It’s amazing that this information was out there for so long before anybody in baseball took any notice. But let’s get back to the issue of why so few sporting novels tell it straight, rather than creating myths or telling jokes. Perhaps the answer is that there’s no call for the service that they would provide. If you want to identify with protagonists in a sporting narrative, what’s wrong with the real thing? In the modern world, sports enthusiasts have every opportunity to follow the real-life fortunes of their sporting heroes. Perhaps this crowds out any demand for fictional substitutes. The trouble with this theory is that there are plenty of successful sporting fictions outside the world of grown-up novels. Take children’s fiction for a start. A lively tradition of novels has long been available for young sports fans. P.G. Wodehouse himself started with cricket stories set in public schools, and in the 1930s John R. Tunis matched him in the States with a series of baseball stories featuring the Brooklyn Dodgers. Contemporary equivalents include Michael Hardcastle, particularly his soccer stories featuring Gary Ansell, and John Feinstein’s sequence of thrillers set across a range of American sports. Movies also seem to have no difficulty in telling sports stories. Some of these are real turkeys, of course: Knut Rockne: All-American with Ronald Reagan; the later Rocky movies (though there’s nothing wrong with the original); The Legend of Bagger Vance; Escape to Victory. Still, for every bad sports movie there are plenty of good ones. My favourites include The Pride of the Yankees, Breaking Away, Bull Durham, and the glorious Tin Cup. (What about Martin Scorcese’s Raging Bull? Many would rank that top. I can recognize its virtues, but I never warmed to it. When I was a kid in South Africa in the 1950s, I was a junior boxer and a huge fan. Sugar Ray Robinson, Rocky Graziano, Jake LaMotta – the very names glowed in lights from across the ocean. But to Scorcese, LaMotta was a slob sitting in a kitchen in his vest. I couldn’t help feeling that he didn’t properly appreciate the stature of his subject.) Anyway, whichever films we rank as our favourites, there’s no doubt that cinema, along with children’s fiction, lends itself to realistic sporting narratives. So why can’t ordinary sports novels fill this role too? It can’t be that there in no demand for stories that hinge on who wins and loses.

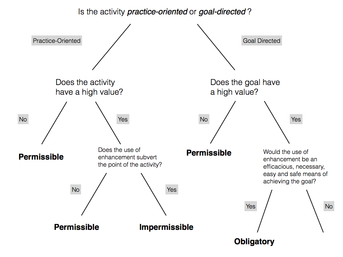

I think I have an answer. The clue lies in the few grown-up books that do succeed as straight sports novels. Here are a handful of proper books where the results of sporting contests matter This Sporting Life by David Storey; Fat City by Leonard Gardner; North Dallas Forty by Pete Gent; The Rider by Tim Crabbe. No doubt there are more. I certainly haven’t read every novel with a sporting theme. But if there are other straight sports novels worth reading, I bet that they share a feature with these four. The authors will know their subject matter at first hand. They will have lived the life they are writing about. Storey was a professional rugby league player with Leeds (now Leeds Rhinos) for five years in the 1950s; Gardner grew up around the boxing gyms in Stockton, California and fought himself; Gent played wide receiver for the Dallas Cowboys from 1964 to 1968; Krabbe was a top amateur cyclist who competed in 100-kilometer-plus road races. As any reader will quickly discern, not a page of their books could have been written without this first-hand experience. Writers of novels need experience to supply the background. In films and children’s fiction, the action can be graphic and sketchy. But novels are necessarily denser, even those without literary pretensions. You need details to add verisimilitude to the narrative. That is why sporting novels written by fans rather than players inevitably collapse into fables or jokes. Without any direct acquaintance with their topics, non-athletes are unable to sustain a realistic treatment. They need to fabricate a world to keep the story going, and find themselves with the choice between fairy-tale or farce. So in the end there’s an obvious solution to our original puzzle. The reason good sports novels are so thin on the ground is that they need writers who have both been serious athletes and are capable of writing fiction. Each category is small enough on its own. Their overlap must be tiny. As a group, novelists are not known for their athletic prowess. Nor are committed athletes the first constituency you would turn to unearth literary talent. If you think about it, it’s something of a miracle that there are any good sports novels at all. The two essential qualifications for writing them pull strongly against each other. We should be grateful for the few that we do have. This post is not one of my usual essays on sport and philosophy, but rather the latest edition of Philosophers' Carnival, a digest of each month's best posts from the philosophy blogosphere, which I was very pleased to be asked to host for September. First up, as ever was, we have Hilary Putnam, who a few months ago delightfully started blogging on his own site Sardonic Comment, and whose latest post puts empirical pressure on the transparency argument for representationalism about sensory experience. Then I would like to take you to two posts which in different ways query the cogency of western attitudes to eastern philosophy. Eric Schwitzgebel's The Splintered Mind argues that there's no good reason for us not to know our classical Chinese philosophy, while in The Indian Philosophy Blog Amod Lele objects to the apparently self-hating double standard that disallows western but not internal reinventions of Indian philosophical traditions. On the mathematical philosophy blog M-Phi, Richard Pettigrew puts L.A. Paul's recent book Transformative Experience through the wringer of meta-decision-theory. There are two posts, on epistemically and personally transformative experiences respectively, and both of them are followed by some illuminating exchanges between Laurie herself and Richard. Last month's host of the Carnival, John Danaher of Philosophical Disquisitions, makes a start on constructing an ethical framework for the use of enhancement drugs, and encapsulates his conclusions in the flow chart below. Over at the communal blog PEA Soup, Antti Kauppinen wonders about the status of rage as a moral emotion--an excellent topic, indeed one which moved me to chip in with a Comment myself.

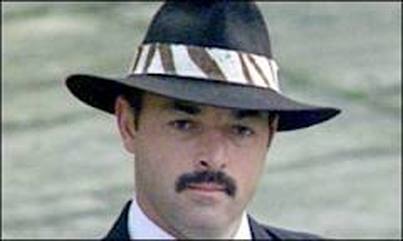

'Aesthetics is for the artist as Ornithology is for the birds' said Barnet Newman in 1954, and this month James Harold was the guest blogger on Aesthetics for Birds, arguing that ethical criticism of art should stop bracketing the causal consequences of works of art. To wrap up, allow me to give a plug to your two hosts, namely Tristan Haze, who runs Philosophers' Carnival, and myself. Tristan's own blog is Sprachlogik. He has been developing the idea that meaning is 'granular' and here he enlists some of Quine's thoughts in support of this theme. And right now you are on my own blog, More Important Than That, where my most recent post (right below) explores the significance of team reasoning in sport and elsewhere. Oh, and don't forget that next month Philosophers' Carnival will be hosted by Tristan himself on Sprachlogik--he does this every October--and that you can propose any posts that grab your attention over the next month by filling in the nomination form. This one is especially for Liverpool fans and legal eagles. But it also carries some general morals for anyone interested in the relations between the law, morality, and the jury system. Remember Bruce Grobbelaar, Liverpool goalie in the 1980s and 90s? Big moustache, did that wobbly knees thing in the 1984 European Cup final, looked like he ran some dodgy Zimbabwean safari firm? Well—for a while he did run a dodgy Zimbabwean safari firm, and that turned out to be the start of his troubles. In the early 1990s, while still playing for Liverpool, Grobbelaar met a fellow Zimbabwean, Christopher Vincent, who induced him to invest £55,000 in a safari camp. When the business failed, the resourceful Mr Vincent, loath to lose his meal ticket, recalled some late-night snippets Bruce had revealed about shady dealings with betting rings, and went to the Sun with the story. The newspaper promptly equipped Vincent with tape recorders and cash. Secret recordings were made in borrowed apartments. And in due course the Sun ran a series of big splashes alleging that Grobbelaar had taken money from Vincent and others to throw games. Wobbly knees European Cup final 1984 Taking bribes to fix matches is a criminal act, and so soon afterwards Bruce found himself in the dock of Winchester Crown Court. However, the prosecution struggled to secure a conviction. In a first trial the jury failed to reach any verdict, and in a retrial later the same year another jury acquitted Grobbelaar on one charge and couldn’t agree on another—at which point the prosecution gave the whole thing up as a bad job. Grobbelaar did well to escape jail. There was plenty of evidence against him, and the fact that Vincent had been an agent provocateur was no defence. Moreover, it was hard to attach much credence to Grobbelaar’s story that he had only been playing along with Vincent to find out who was behind him, especially as this tale didn’t answer the allegations involving other betting syndicates. The only real thing going for the defence was that the instrument of Grobbelaar’s downfall was the Sun. As the jury would have known, the Sun had been conducting a vendetta against Liverpool football club for some years. After the Hillsborough disaster in 1989, it repeatedly trumpeted the smears about Liverpool fans that the police had invented to cover up their own responsibility for the ninety-six deaths. Nor was it above bringing Grobbelaar’s wife Deb and children into the bribery splashes. “Shameful secret has Deb in tears” ran one headline, and another article reported that Grobbelaar had refused to answer such reporter’s questions as "How much of what's been happening have you told the children about? Have they been getting a hard time at school?" We can imagine that the jury might well have felt disinclined to kick a man who’d been subject to such treatment. Grobbelaar’s successes in the criminal courts encouraged him to go on the offensive. He sued the Sun for libel, and in 1999 a jury found for him in the High Court and awarded him £85,000 in damages. (I hope you aren’t getting tired of all these trials. I warned you that this was one for the legal buffs. There are still two more verdicts to come.) The Sun promptly appealed against the libel decision, on the grounds that the jury’s verdict was ‘perverse’. This was somewhat unusual, in that jury decisions are close to sacrosanct in English-based common law, and normally you can’t appeal just on the basis the jury got it wrong. But in certain kinds of cases you can get a jury verdict overturned if you can show that ‘no reasonable jury, who had applied their minds properly to the facts of the case, could have arrived at the conclusion which was reached’. And that’s what the Sun successfully argued in the Court of Appeal. Remember that in civil libel cases the defendants—the alleged libellers—only need to prove the truth of their claims ‘on the balance of the probabilities’, and not ‘beyond the reasonable doubt’ required for a criminal conviction. So the Sun could concede that their incriminating tapes and other evidence might not have been enough to compel the criminal juries in Winchester, and yet insist that any reasonable person would take them to show that Grobbelaar’s guilt was at least more probable than not. The Court of Appeal agreed, striking down the jury’s verdict and the £85,000. We aren’t done yet. By now Bruce had the bit between his teeth, and opted to take it all the way to the top, to what would now be the Supreme Court, but was then the Law Lords. Once they got their hands on the case, the Lords of Appeal in Ordinary started by thinking a bit harder about what the original libel jury could have had in mind. They noted that there were two distinct parts to the Sun’s allegations. In the first place the Sun had said that Grobbelaar had been accepting bribes. And then they had said that he had let in goals on purpose. The Law Lords came to the view that the jury must have thought that, while there was plenty evidence for the first claim, there wasn’t any for the second, and that they had found against the Sun for that reason. In truth, not only was there no evidence that Bruce had let in goals, but good evidence that he hadn’t. Let me quote from the Law Lords’ eventual written opinions. (You can read all their 20,000 words at http://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/ld200102/ldjudgmt/jd021024/grobb-1.htm.) Here’s a passage about witnesses at the libel trial: “There was expert evidence strongly supportive of the appellant's evidence from Mr Bob Wilson, formerly a professional goalkeeper of the highest standing, and Mr Alan Ball, formerly a professional footballer of renown who had been the appellant's manager at Southampton. Mr Wilson saw no evidence of anything other than good (and on occasion outstanding) goalkeeping in any of the five games. Mr Ball saw nothing odd or suspicious in the appellant's play in either of the two Southampton games, both of which he had watched.” Yes, these dudes really do write like that. ‘Formerly a professional footballer of renown.’ Alan Ball. I am sure that most senior judges are regular human beings who only use such phrases that because they enjoy celebrating the old forms. But in this particular instance, as we are about to see, the sitting Lords of Appeal in Ordinary did little to dispel the impression that they were a bunch of old fogeys who’d been living with their pompous phraseology for a long time, handing down rulings and feeling entitled to impose their views on the rest of us. Taking account of the expert evidence from Ball and Wilson, the Law Lords upheld the original jury’s verdict that the Sun was guilty of libel. They reasoned that the jury must have felt that the Sun hadn’t shown that Grobbelaar had let in goals on purpose, and moreover that this justified an award of £85,000. However, the Lords disagreed strongly with jury about the second part. They allowed that the Sun hadn’t proved their claims about the goals, and that these claims were libellous. But they didn’t think that these claims damaged Grobbelaar in any substantial way—on the grounds that his name was already mud. As they saw it, he had already been exposed as someone who had taken bribes on the promise of fixing games. That he was then falsely said to have let in goals as well could scarcely damage him further, as he had no reputation left to protect. So they awarded him a nominal £1 and required him to pay all costs. Grobbelaar declared himself bankrupt soon afterwards.

I don’t know how it was for you, but when I first read the original Sun stories I was shocked. It wasn’t the bribery that shocked me, though, so much as the thought that Bruce might have thrown games on purpose. All right, taking bribes isn’t very nice, and certainly it lowered Bruce considerably in my estimation. He was clearly hanging out with an unsavoury crowd. But that wasn’t in the same ball-park as losing games on purpose. How could he have let down his teammates, the fifty thousand desperate fans on the Kop behind him, the whole history of Liverpool football club, just for a few pounds? No punishment would be enough for someone who did that. He should be cast out and left to wander in the wilderness for the rest of his days. Well, that’s not how the Law Lords saw it. Lord Hobhouse was quite explicit on the point. “Corruption is much more serious than letting in goals deliberately. The one is a criminal offence and the other, as such, is not.” Perhaps it’s not surprising that men who have spent their whole life administering the law should regard breaking it as a paramount sin. But someone who was brought up in Zimbabwe, or on the wrong side of the tracks in Liverpool, or in many other places, might well take a different view, holding that while a lot of laws are sensible, a lot are also designed to preserve the interests of privileged groups, and that therefore breaking the law isn’t necessarily the worst thing in the world, compared with cheating your mates, say, or letting down the fans. Still, this is a topic on which different opinions are possible, and the eminent Lords were perfectly entitled to their view. What they weren’t entitled to do, though, was correct the original jury on the matter. The law of libel is complicated. An appeal court has the power to reduce the amount of damages awarded by a jury if they feel that it is an excessive departure from previous such awards. But that clearly wasn’t the issue in this case, though the Law Lords pretended that it was. It wasn’t that they felt that the jury had misjudged how much money to award for a serious libel. Rather they felt that the jury were wrong to think that there was a serious libel in the first place. And this was absolutely not their business. The law of defamation says that your published words are libellous if they will ‘lower someone in the estimation of right-thinking members of society generally’. By the Law Lords' own analysis, the jury felt that the allegations that Grobbelaar had thrown games on purpose indeed lowered him substantially in the eyes of right-thinking people generally, even against the background of his taking bribes. I myself think that the jury was absolutely right about this. To normal right-thinking people, the idea of Grobbelaar deliberately missing the ball in front of the Kop would be horrendous, far worse than taking bribes. But that’s not the point. Whether the jury was right or wrong, it was a matter for them to decide, and the Law Lords had no right to substitute their own view of what ‘right-thinking members of society generally’ would think for that of the jury. I am not sure what to make of this. Whatever their other failings, the Law Lords were not stupid, and they must have known in their hearts that they were riding roughshod over the law on juries. It is a basic principle of our legal system that, ‘perversity’ aside, appeal judges cannot correct the conclusions that juries reach about matters of fact. In the end, it is hard not to see something almost hypocritical in their decision. Having appealed to the importance of the law against bribery to override the jury’s view that Grobbelaar had been badly libelled by the standards of everyday morality, the Law Lords then allowed their own moral attitudes to override their duty to the law. Of course the law wasn’t the only thing damaged by the Law Lords’ decision. It also ruined Grobbelaar financially. But Bruce is nothing if not resilient. Over the years he has moved around, coaching a series of teams in South Africa, England and then Canada, where he is now settled. He remains a great favourite at Anfield, turning out regularly for the 5 Times Liverpool Legends team (five times European champions, if you’re wondering), and in 2006 he was voted number 17 in the official club poll of all-time favourite players. Clearly the Liverpool fans don’t think that he let in goals on purpose. Nor do I. |

AuthorI am interested in nearly all sports from around the world. I used to play some but not so much any more. Previous Posts (only 6 & 17 are still live links-see main text) 1 Choking, The Yips and Not Having Your Mind Right 2 Mutual Aid and the Art of Road Cycle Racing 3 Why Supporting a Team isn't Like Choosing a Washing Machine 4 Civil Society and Why Adnan Januzaj Should be Eligible for England (Though He Isn't) 5 Why Does Test Cricket Run in Families? 6 Bruce Grobbelaar and Middle Class Morality 7 The Importance of Being Focused 8 Professional Fouls and Political Obligation 9 Morality, Convention and Football Fakery 10 Give Me a Defender of Amateur Values and I'll Show You a Hypocrite 11 Game Theory, Team Reasoning, and a Bit about Sport Too 12 Sporting Geography, Political Geography and the Ryder Cup 13 Competitive Balance, Coase's Theorem and Sporting Capitalism 14 Bill Shankly, Noam Chomsky and the Value of Sport 15 Sporting Teams, Spacetime Worms, and Israeli Football 16 Race, Ethnicity and Joining the Club 17 Myth, Humour and the Strange Dearth of Sports Novels Archives

March 2017

CategoriesBlogrolling

Stephen Law

Editor of Think, philosophy, humanism Think Tonk

Clayton Littlejohn, epistemologist and colleague Philosophers' Carnival

Monthly digest of highspots from the philosophy blogosphere Philosophy Football

"Sporting outfitters of intellectual distinction." T-shirts and theses about football. |